‘Hungry people are angry people’

The zinc roofs of farm workers’ homes in the eastern Free State are peppered with stones to keep them from blowing away. No one wants to risk screwing their zinc down because they could be evicted at any moment.

No one but Anton Chaka, who was tired of the transience of his life. He had lived in Naledi Village in the Maluti mountains near Ficksburg for 45 years.

Tired of moving

“How do you build a house when the land doesn’t belong to you? If I had a dispute with the landowner, I would have to take the roof and the windows of my house and leave. But I was tired of moving,” says Chaka, who risked his life-savings on building a house and screwing down the zinc roof.

“I was always working for other people, planting and harvesting but this food was not accessible to us. Mielie meal was our main diet and milk from our cattle. We did not really eat vegetables, maybe some wild morogo (spinach) every now and then. People had lots of sicknesses because we were not eating healthily.”

Meanwhile, Japie Lephatsi’s father never wanted his son to work on the farms. But when he died, Lephatsi had to quit school and find work at President Steyn Mine in Welkom to survive.

He hated it. Four months into the work, he went to the mine office and explained: “I am not lazy, not scared. I don’t have problems. But I do not see the point of that work, clearing the rock every time. If I leave the mine, how would that work help me?”

Lephatsi laughs at the courage he showed as a young man. A few months after blurting out his truth, he was offered a job in the change-room for white miners and eventually worked his way up to becoming an electrician.

Whenever he could, he would escape from the mine and head home to Naledi Village, nestled in Rustler’s Valley: “My mother worked as a chef. She earned R15 a month at this lodge. I used to help out over the weekends, and they got used to me here.”

Rustlers’ Valley revival

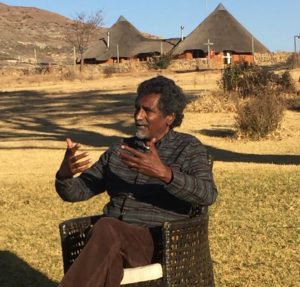

In an historic reversal of fortunes, Chaka and Lephatsi are now leaders of a community-based revival of part of the old Rustlers’ Valley farm, renowned for wild Easter rock festivals back in the day.

Chaka runs the Naledi Village Farmers’ Co-operative, while Lephatsi is in charge of the Earthrise Mountain Lodge, which rents out accommodation and a conference venue.

The revival has been initiated by a powerful trio of activists and friends: former Cosatu general secretary and cabinet minister Jay Naidoo; former Greenpeace executive director Kumi Naidoo and former trade unionist and Amnesty International advisor Gino Govender.

In 2013, the trio’s Earthrise Trust bought Rustlers’ Valley, which had fallen into disrepair following a fire and the death of the owner.

“We were looking for a safe and sacred inter-generational space to enable us to try to find solutions to the problems facing us globally and nationally,” says Jay Naidoo, of the trio’s desire to put their politics into practice.

“None of us expected the challenges of today – of mass hunger, socio-economic injustice and unemployment,” says Naidoo quietly. “We are two decades into democracy, where changing the apartheid system was hailed as a transformation miracle. But there has been insufficient change in the realities of the majority of the people. There is mass unemployment, very poor quality of schools. White farmers still load black workers on the backs of their bakkies and pay them R50 a day.

Village without hope

“When we came here, Naledi Village was without hope. A microcosm of apartheid, people were struggling to survive. The first liberation was political liberation, but the second liberation must result in people getting access to land and the economy.”

[quote float = right]There has been a coup d’état on our plates, explains Naidoo. “Many families in South Africa face the double burden of malnourishment and obesity.”

One of the first things the Earthrise Trust did was to transfer 42 hectares of land to a community trust owned by the 170 residents from the 44 households of Naledi Village to ensure that no one could ever evict them again. Twenty eight hectares is being cultivated, while the rest is being used to graze cattle, and for small businesses and homesteads. Profits from farming, the lodge, a brick-making enterprise and bakery are being ploughed back into the community.

“The biggest problem facing Naledi village is that they have run out of labour to run the various enterprises,” says Naidoo.

Chaka takes Health-e to the store that holds the remains of the co-op’s first harvest of sugar beans. Most of the 10 tons of beans have already been sold or donated to surrounding villages. The co-operative is also growing tomatoes, spinach, green peppers and water melons.

Opportunity to grow food

“The main thing is, we now have access to land and have the opportunity to grow food for ourselves,” says Chaka. “There are a lot of unemployed people. Hungry people are angry people.”

Every week, the co-op donates food to the local crèche and school and Chaka says there has been a noticeable improvement in the children’s health.

The farmers have already had to face many challenges – including searing heat and invasive weeds. Nonetheless, they have resolved to keep their land free from chemicals and pesticides to grow the healthiest crops possible. In addition, they are growing diverse crops to ensure they eat balanced diets, building seed banks and re-introducing medicinal plants to the farm.

“There has been a coup d’état on our plates, explains Naidoo. “Many families in South Africa face the double burden of malnourishment and obesity. The fast food industry is poisoning us. We have an explosion of diseases that never faced us in the past: diabetes, hypertension, cancers, bone disease, heart disease. Communities need to go back to the diverse diets they had many generations ago.”

High eviction rate

The Department of Rural Development is in the process of registering the village’s community property association (CPA) as a legal entity to act on behalf of the villagers.

Dineo Gaobepe, assistant director in department, says that the district where Naledi Village is situated, Thabo Mofutsanyane, has one of the highest eviction rates of farm workers in the country.

“It is very rare where we are called to help people who are getting land from landowners. This is a good example of how land reform can happen. Many CPAs are not socially cohesive, but this one has social cohesion,” said Gaobepe.

While the Earthrise trustees have been able to facilitate a lot of help for the village – including a grant from Old Mutual which enabled them to buy farming equipment – it has been unable to secure a reliable source of water for them.

Four years ago, the village’s water supply was cut off by the new owner of a neighbouring farm, Thaba Thabo (ironically meaning “mountain of happiness”). He claimed that the water that they had always had access to from a nearby mountain belonged to him, and that villagers would need to pay R2 500 a month for it.

“My father laid the pipes to get this water,” says Lephatsi. “How can he claim the water we have always used belongs to him?”

Water cut off

Young men in the village were so angry that they wanted to ambush the farmer but the trust’s leaders dissuaded them from doing so. But the situation has still not been resolved. Although the Setsoso Municipality has told villagers that this was illegal, it has not acted against the farmer. Instead, it sent engineers to the village twice to sink boreholes – and twice the engineers refused to listen to villagers about where the water was and sunk boreholes that have not yielded water. Now, it sends water trucks intermittently.

Naidoo’s frustration is palpable: “What we have in this country today is a sense of impunity that has spread to the rest of the political elites or the economic elites to a point where a farmer thinks it is his right to cut off water to the village of Naledi. We have a municipal official feels he doesn’t care a damn, he won’t loose a minute’s sleep, that three years later, 170 people, a third of them being children, have no access to drinking water.”

“Government and the private sector are pumping billions into industrial agriculture. The shops are overflowing with food, but at a household level, where one in three people are unemployed, millions of people can’t put food on their table. They need support to become small farmers.”

Naidoo believes the Earthrise revival could “definitely be replicated if there was political will” and that there is an urgency to do as “we are sitting on a time bomb, unemployment, hunger and no access to water”. – Health-e News.

Author

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Unless otherwise noted, you can republish our articles for free under a Creative Commons license. Here’s what you need to know:

You have to credit Health-e News. In the byline, we prefer “Author Name, Publication.” At the top of the text of your story, include a line that reads: “This story was originally published by Health-e News.” You must link the word “Health-e News” to the original URL of the story.

You must include all of the links from our story, including our newsletter sign up link.

If you use canonical metadata, please use the Health-e News URL. For more information about canonical metadata, click here.

You can’t edit our material, except to reflect relative changes in time, location and editorial style. (For example, “yesterday” can be changed to “last week”)

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. Health-e News understands that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarise or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

You can’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

If you share republished stories on social media, we’d appreciate being tagged in your posts. You can find us on Twitter @HealthENews, Instagram @healthenews, and Facebook Health-e News Service.

You can grab HTML code for our stories easily. Click on the Creative Commons logo on our stories. You’ll find it with the other share buttons.

If you have any other questions, contact info@health-e.org.za.

‘Hungry people are angry people’

by kerrycullinan, Health-e News

November 6, 2017