Winning the fight against TB

Dr Laura Trivino-Duran of Médecins sans Frontières (MSF), commonly known as Doctors Without Borders, says the mortality rate related to the injectables regimen treating TB was high and alarming. “It became so obvious that we couldn’t continue with the injectables, then the South African government decided to move ahead and get rid of the injectables fully and implement the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommendation in terms of SHORRT course regime without injectables.”

SHORRT stands for shorter highly-effective oral regimens for rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis therapy. It is now offered to all rifampicin resistant–tuberculosis (RR-TB) patients as a first option, and as of January this year, more than 95% of people living with RR-TB have been offered this regimen.

Global guidelines to treat TB

The WHO estimates that 480 000 people developed multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) in 2015 and 190 000 people died as a result of it. “MDR-TB cannot be treated with the standard six month course of first-line medication which is effective in most TB patients. Patients with rifampicin-resistant or MDR-TB are treated with a different combination of second-line drugs, usually for 18 months or more,” the organisation says.

WHO updated its treatment guidelines for drug-resistant TB in May 2016 and included a recommendation on the use of the shorter MDR-TB regimen under specific conditions.

“South Africa is contributing, regionally and globally, to the biggest number of patients in the SHORRT regimen,” says Trivino-Duran. She says the great thing about SHORRT therapy is that “you don’t have to go to the clinic every day because you don’t need to have an injectable every day”.

Southern African countries unite

At a recently held two-day workshop in Johannesburg hosted by South Africa’s health department and MSF, professionals from Southern Africa came together to see how can they support each other for the enrolment of the SHORRT course regimen to be successful.

“As a region we need to have a conversation whereby we’re all asking for the same things, somehow we’re all struggling with the same problems such as funding for drugs, training, transport and many more but funding is not the only issue, there is also other issues that are important to overcome,” says Trivino-Duran.

Eswatini is set to introduce the SHORRT therapy early next year, without having done a clinical trial or implementation research due to lack of funding.

“As Eswatini we introduced the SHORRT injectable base regimens in 2014 and we’ve observed that it improved the treatment outcomes but we still noted that about 60% pf patients were experiencing problems such as hearing loss. And we also noted the high mortality rate which was above 10%, which is why moving forward we want to introduce the short oral regimens beginning next year February,” says Nonhlanhla Dlamini, Programmatic Management of Drug Resistant TB (PMDT) coordinator in Eswatini.

She adds: “The challenge we faced was mainly funding to implement the operation research but moving forward, I don’t think we will have any problems because the drugs which we will be using are the ones we are already using in the long regimens the 18-20 months’ programme. Currently we have already developed the protocol and starting with the ethics committee and we are waiting for the approval.”

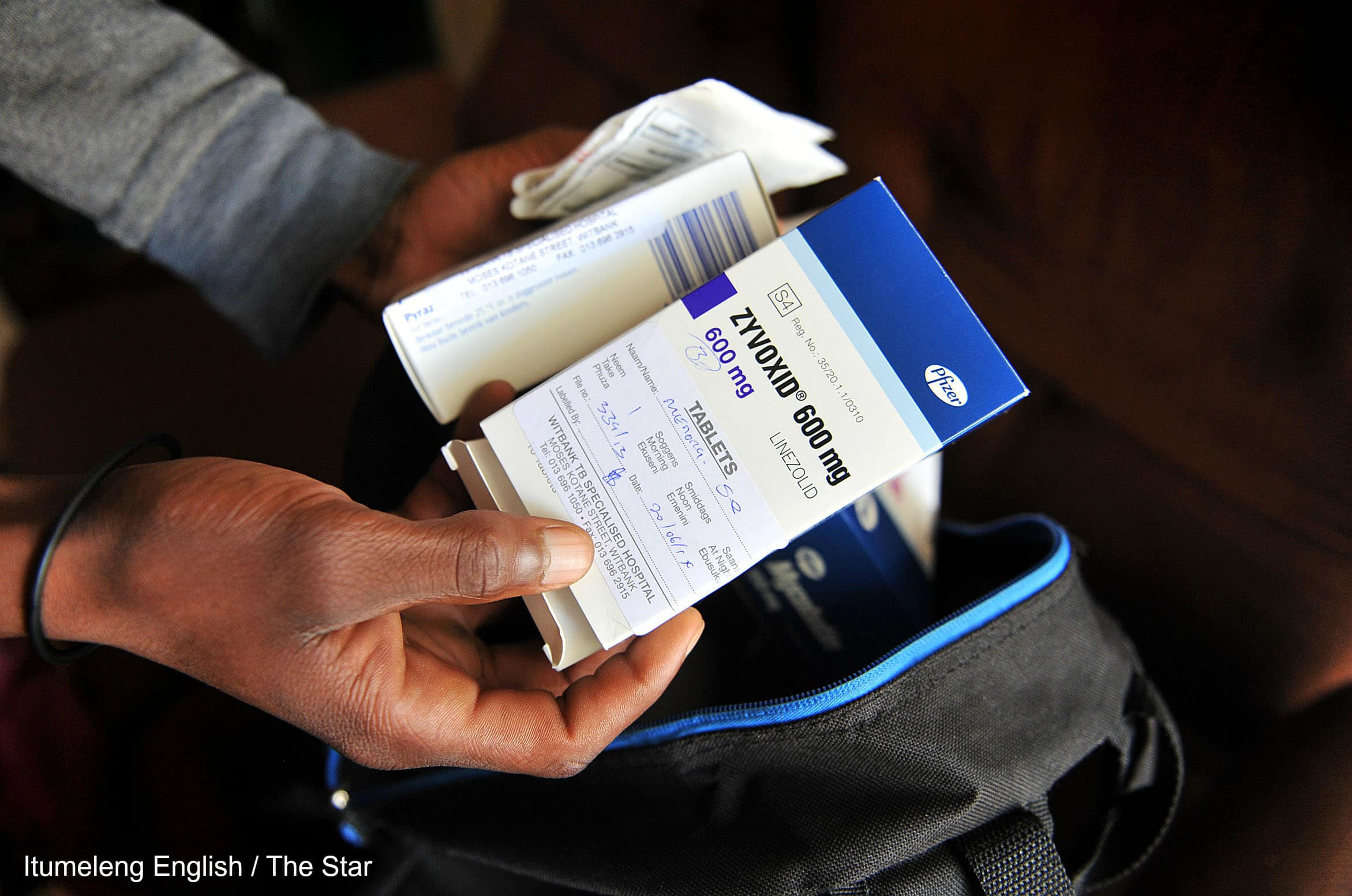

Dlamini says that they will only start rolling out the therapy at a few health facilities, while hoping to have the treatment available throughout the country at the end of 2020. “We are starting with a pilot of about five facilities that are two of the richest in Eswatini and after that we will roll out to the entire country but we have not yet implemented a clinical trial or any other operational research. The regimens that we are planning to implement is bed aquiline and linezolid for a period of nine to twelve months.”

In Lesotho they have begun with the clinical trial for SHORRT-therapy but they are still faced with a challenge of patients who cross the border to seek better medical services in South Africa. MDR-TB programme manager at Partners in Health in Lesotho, Lawrence Oyewusi says that they have seen a reduction in mortality rate since they have put the SHORRT-Therapy on clinical trial in their health facilities.

“Lesotho has not really adopted the use of SHORRT regimens but we are doing it under clinical trial. But the clinical trial is completely different from operational research… when you do things under clinical trial there are so many things you need to look at, such as, monitoring the patients very well. So far we have enrolled a lot of patients and I think they are doing so well because if you look at the programme in Lesotho the mortality rate used to be very high at the range 30-33% but ever since we started using the new drugs, the mortality rate has been reduced to about 17% now. With the clinical trial we have seen a lesser mortality rate,” says Oyewusi.

He says the clinical trial will take about five years because it is also occurring in other countries.

“The enrolments will be for about two and a half years and the follow up will be for two years as we do not want to give a SHORRT regimens without being sure if patients will relapse or not [so] we have to do follow ups but after the trial it is something which everyone is looking forward to. The longer regimens which we used to use is very toxic as it has a lot of toxic drugs in there but now things are changing as Instead of treating patients for 18 months you can actually reduce it to nine months and save a lot of money.”

Progress in South Africa too

According to Dr Norbert Ndjeka, director of National TB and Management Cluster in South Africa: “When the country started using bedaquiline, we observed that the death rate was coming down slowly. We also noticed that we didn’t have any option for patients who developed ototoxicity so we felt that maybe [it] is better than not to give an injectable to individuals who were [reacting] on toxicity.” Before that, Ndjeka says, patients had to choose to either to remain deaf or die. “We don’t like those options.”

He says this is why South Africa started using bedaquiline and there was an improvement in treatment success rate and hearing loss also decreased. He tells Health-e News that they carried on with the same logic in the shorter regimen. “In our shorter regimen we achieved a treatment success rate of 67%, it has never happened before in South Africa, everything used to be below 50%.” Ndjeka says if everyone could be on this regimen, the country will achieve 75% treatment success rate.

Jennifer Furin of Harvard Medical School says 500 000 people become sick with RR-TB each year, while only 156 071 (31%) are diagnosed and put on treatment. Only 51% of those diagnosed with TB have their strains tested for rifampicin resistance and only 59% of those individuals received testing for second-line medications.

“New and repurposed drugs such as bedaquiline and linezolid are saving lives with shorter regimens leading to potentially more tolerable treatment as injectable-free regimens reduces exposure to toxic medications,” says Furin. – Health-e News

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Unless otherwise noted, you can republish our articles for free under a Creative Commons license. Here’s what you need to know:

You have to credit Health-e News. In the byline, we prefer “Author Name, Publication.” At the top of the text of your story, include a line that reads: “This story was originally published by Health-e News.” You must link the word “Health-e News” to the original URL of the story.

You must include all of the links from our story, including our newsletter sign up link.

If you use canonical metadata, please use the Health-e News URL. For more information about canonical metadata, click here.

You can’t edit our material, except to reflect relative changes in time, location and editorial style. (For example, “yesterday” can be changed to “last week”)

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. Health-e News understands that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarise or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

You can’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

If you share republished stories on social media, we’d appreciate being tagged in your posts. You can find us on Twitter @HealthENews, Instagram @healthenews, and Facebook Health-e News Service.

You can grab HTML code for our stories easily. Click on the Creative Commons logo on our stories. You’ll find it with the other share buttons.

If you have any other questions, contact info@health-e.org.za.

Winning the fight against TB

by jamesthabo, Health-e News

November 29, 2019

MOST READ

Social media for sex education: South African teens explain how it would help them

Prolonged power outage leaves hospitals in the dark for two days

There’s more to self-care than scented candles or massages, it’s a key public health tool

Access to clean water and stable electricity could go a long way to addressing rising food poisoning in SA

EDITOR'S PICKS

Related

A new strawberry-flavoured HIV treatment for children could improve adherence

Gauteng health facilities face shortages of crucial medication