Sustainable Development Goals: Utopian dream or plausible plan?

Born in Springs on Johannesburg’s East Rand, Matshidiso Moeti grew up watching her doctor parents tend wounds and set bones in nearby KwaThema. The little girl destined for big things learned early that injustice and inequity were their own sorts of plagues.

“My parents were doctors in the township and ran a practice…so one was aware of the struggles of families in the community,” she said. “Even by the time I was 7 or 8 years old, I remember reading The Post newspaper and being very much aware of the political system in place, aware of what was essentially an unjust society… this influenced me a lot.”

When Moeti’s parents moved to Botswana, her father took to the bush conducting small pox eradication campaigns. Her mother took a post at the Botswana Ministry of Health, which led her to what is now Kazakhstan for a work meeting in 1978.

When Moeti’s mother returned home, she had been a part of history. Her meeting had adopted the Alma-Ata Declaration, which made the case for universal health coverage. It would also shape her daughter’s destiny.

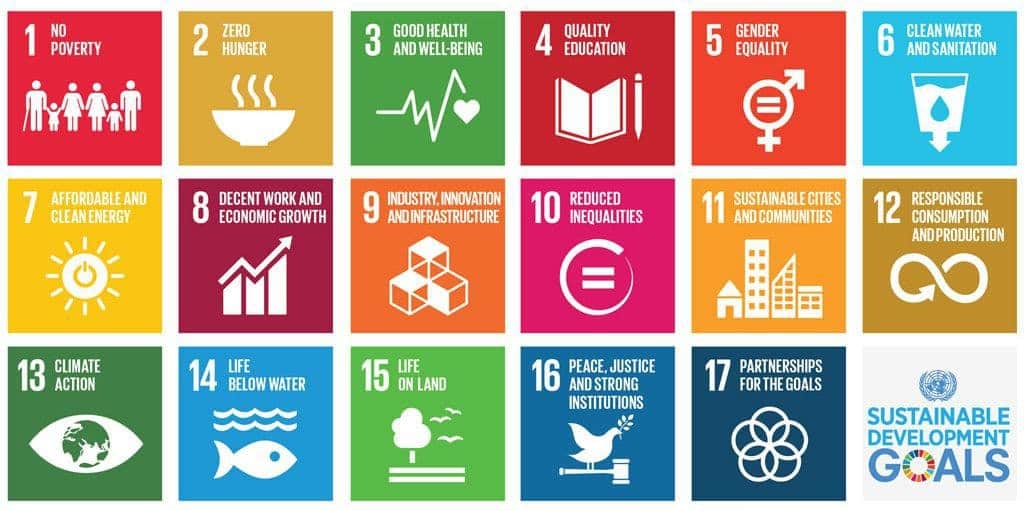

Universal health coverage is one of the 169 targets and 17 goals comprising the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by the United Nations on Friday 25 September. They take over from the eight Millennium Development Goals adopted 15 years ago.

The product of hard negotiations and almost 100 international consultations, the SDGs are sufficiently vague to read like a Utopian laundry list. The real meat likely to guide governments’ and donors’ money is hidden in the SDG’s targets, which include the roll out of universal health coverage.

But what the world committed to in New York this weekend, Africa has been slowly mulling over for the last decade as more countries including South Africa turn to universal health coverage as a way of improving health outcomes and stamping out deadly inequalities.

From Nigeria to Rwanda, African countries are carving out new ways of dolling out – and paying for – healthcare.

African countries re-imagine universal healthcare coverage

Until recently, the world had two brands of universal healthcare both of which were developed in the early 1900s. The British variety uses general taxes to fund publicly- provided healthcare while its German equivalent relies on household premiums, payroll taxes and private healthcare providers. Countries like Japan, Canada and France all implemented variations on these tunes.

However, in about the last decade developing countries from Latin America, Asia and Africa have begun to create new models of universal health coverage.

Ghana increased value-added taxes by about three percent in 2003 to domestically fund its universal health coverage programme. Nigeria used revenue freed up by debt relief to fund pilot universal coverage programmes for expecting mums and children. Likewise, Sierra Leone removed user fees for mothers and young children in 2010 and saw a 60 percent decline in maternal mortality, according to UNICEF. Mali, Kenya and Rwanda relied on a mix of international and domestic funding to kickstart moves to universal health coverage.

Dr Matshidiso Moeti, the little girl from Springs, is the first woman to lead the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) Africa office as the continent’s health systems seem poised for a revolution – the seeds of which her mother helped to sow decades ago.

Moeti took the reigns in February after being grilled alongside fellow candidates at a meeting of African health ministers in Benin. The meeting included South African Health Minister Dr Aaron Motsoaledi, who put tough questions on universal health coverage to Moeti and others.

“He made a very impassioned plea in his style for the WHO to re-allocate our own internal budget,” Moeti remembered.

What Motsoaledi asked was that the WHO to prioritise universal health care

“We even asked that the WHO Africa region must change its direction,” said Motsoaledi, calling his encounter with Moeti. “In the past, (the WHO) concentrated on vertical disease programmes. We said they must focus on strengthening health systems to implement universal health coverage.”

It was an easy sell to Moeti, whose agenda for health in Africa includes universal health coverage, underpinned by a commitment to equity in access to healthcare that she inherited from her doctor parents all those years ago.

The WHO Africa office recently saw an almost 30 percent increase in its universal health coverage budget, which Moeti says is a good start.

But the SDGs have already drawn criticism from experts and countries alike most markedly because there are so many of them, which may threaten to divide countries’ focuses and money.

In a brief released Friday, international humanitarian organisation Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) expressed concern over what it said could become a bigger gap between international donor commitments and professed goals as shrinking international aid funding stretches to meet more, rather than fewer, demands. Shrinking aid has already led some African Health Ministries of Health to push the burden of funding health onto patients.

“The recent resurgence of proven harmful mechanisms such as ‘user fees’ or out-of-pocket payments in the corridors of some Ministries of Health in Africa is to compensate for dwindling international aid for health,” said MSF, adding that the language of sustainability underlying new goals hints at an increased push for countries to foot their own bills and could jeporadise health in poor countries. “This is totally contradictory to the concept of universal healthcare, and a major cause for concern”

South Africa must unlock private sector money

In regard to South Africa, both Motsoaledi and Moeti have separately said they are confident we have the money for universal healthcare.

[quote float= right]I am not going to start believing that there is a market force or some other natural process that, without any procedure, a child of 10 days’ old can run a R790 000 bill”

“We believe there is enough money,” said Motsoaledi at a recent UN consultation in Johannesburg. “The WHO recommends that countries must spend five percent of their GDP on health. We are at more than eight percent, which is equivalent to the average in Europe.”

But much of this money is tied up in the private sector. The National Health Insurance will have to unlock that money and those resources.

“The picture here in (South Africa) is very much complicated by the fact that you have a very big private health care sector and you have pricing that is very variable and in the private sector, extremely costly,” admitted Moeti. “I think the reality is that the country will always have a private healthcare sector but it is about how it is rationalised in a country like this that is going to make all the difference.”

It is a challenge that other BRICS countries have already had to face. In India, for example, the introduction of universal health coverage led government to allow private health insurers to bid to implement state health coverage. It is also why the current Market Inquiry into the Private Healthcare Sector is so important.

“The health care system is unaffordable,” said Motsoaledi recently. He went on to describe a case of triplets reported in the media. “Those three kids were 10 days’ old but they had already run a bill of R790 000.

“I am not going to start believing that there is a market force or some other natural process that, without any procedure, a child of 10 days’ old can run a R790 000 bill,” he told Health-e News.

The missing ingredient?

[quote float= right]Social solidarity may be the one ingredient for a national health insurance that no one has measured but everyone should care about

According to Department of Health officials, the minister has developed a penchant for the writings of Dr Paul Farmer and quotes the Harvard University Professor of Global Health and Social Medicine in discussions. Interested in understanding how social and economic conditions impact health, Farmer has made a name for himself by pioneering new community-based models of health care in low-resource settings.

Farmer’s interest in social determinants of health also resonates with Moeti, who has changed the structure of the WHO Africa office to ensure that her second in command is responsible for overseeing reporting on the social determinants of health.

In a recent New England Journal of Medicine article, public health experts identified five factors that had influenced the adoption of universal health coverage in six countries, including transformative leadership, economic growth and – hardest to measure of all – social solidarity or citizens’ willingness to expand a welfare state.

The authors mention that qualitative studies have shown that social cohesion has led to lower levels of income inequality, crime and corruption as well as rising rates of per-capita GDP historically.

In a country like South Africa, social solidarity may be the one ingredient for a national health insurance that no one has measured but everyone should care about. If you asked a little girl in the East Rand many years ago, she would probably say she already knew that. – Health-e News.

An edited version of this story was also published by the Daily Maverick.

- Never miss a story. Subscribe to our free, weekly newsletter

- Track South Africa’s National Health Insurance through its first three years

Author

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Unless otherwise noted, you can republish our articles for free under a Creative Commons license. Here’s what you need to know:

You have to credit Health-e News. In the byline, we prefer “Author Name, Publication.” At the top of the text of your story, include a line that reads: “This story was originally published by Health-e News.” You must link the word “Health-e News” to the original URL of the story.

You must include all of the links from our story, including our newsletter sign up link.

If you use canonical metadata, please use the Health-e News URL. For more information about canonical metadata, click here.

You can’t edit our material, except to reflect relative changes in time, location and editorial style. (For example, “yesterday” can be changed to “last week”)

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. Health-e News understands that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarise or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

You can’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

If you share republished stories on social media, we’d appreciate being tagged in your posts. You can find us on Twitter @HealthENews, Instagram @healthenews, and Facebook Health-e News Service.

You can grab HTML code for our stories easily. Click on the Creative Commons logo on our stories. You’ll find it with the other share buttons.

If you have any other questions, contact info@health-e.org.za.

Sustainable Development Goals: Utopian dream or plausible plan?

by lauralopez, Health-e News

September 28, 2015

One comment

It’s plausible with concerted and collective global effort and cooperation.